by Paula Prescod

Place names or toponyms, as they are formally called, are like signposts that tell us a great deal about a nation’s past.

They are a rich source of information on the way political and sociolinguistic powers played out among the different groups of individuals who shared the land throughout its history. Further still, they testify to the linguistic contacts which occurred in these territories, to the geographical features in which these contacts played out, as well as to the motives behind choosing these names or the attitudes individuals had to the places they named.

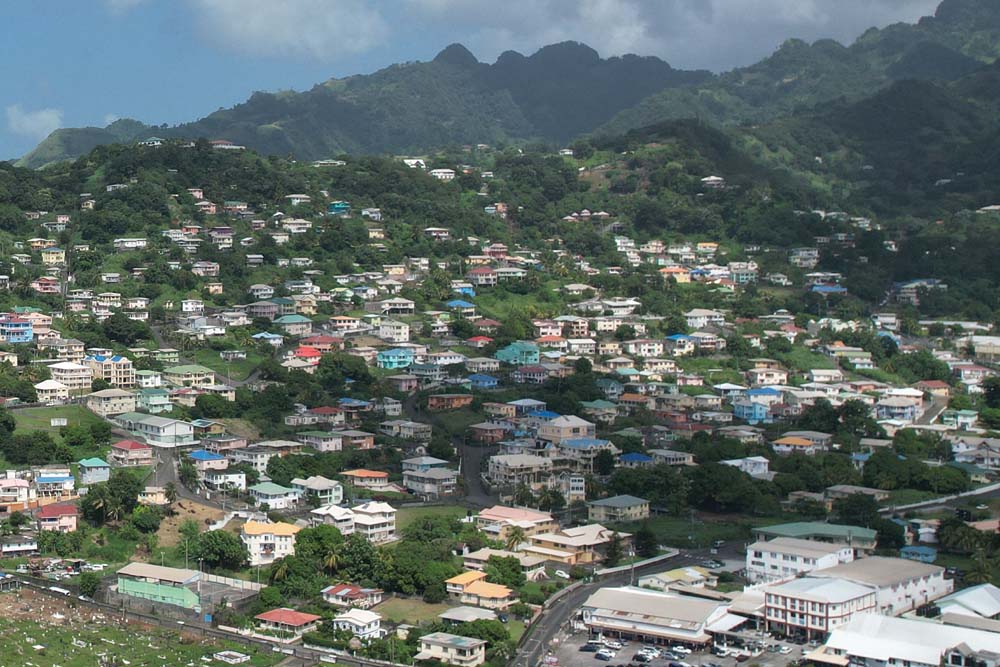

Kingstown was formerly known by its indigenous names Washigunny or Ouashegunny. (photo credit Eldonte Samuel)

If we compared maps of St Vincent and the Grenadines at different eras, we would have a striking indication of the linguistic and ethnic groups that relished the privilege of naming. Byres’ 1773 plan of St Vincent reveals several place names that are not English-sounding. Many of them are indigenous place names that remind us of the Carib past on SVG or the French-sounding place names of their putative allies.

On maps from subsequent periods, like the one drawn by Lucas in 1823, there are far fewer indigenous names. Throughout the centuries, indigenous place names have been replaced by colonial ones, a process which can be referred to as toponymic silencing.

From a socio-political standpoint, it could be argued that attempts to assimilate and acculturate the indigenous population, the African slaves and the indentured workers who came primarily from Madeira and India resulted in the stark absence of place names that would remind THEM of their roots.

For indeed, in many instances, the English-sounding names were simply calqued onto SVG to suit the fantasies of those who had travelled thousands of leagues away from their birthplace. It may well be that those who bestowed the place names were bent on holding on to something that kept their homeland close, symbolically, so to speak. After all, places ground individuals and constitute a powerful marker of identity.

Layou, St Vincent. Layou is an indigenous place name that also exists in Dominica where the Kalinago also made their home. The British tried replacing Layou with Ruthland Bay but the indigenous name stood its ground. (photo credit Clare Keizer)

Several examples of transplanted place names come to mind. Scores of places in England are formed with the suffix -borough which designates a fortified place. Other spelling variants of -borough are -bury, -berry and -boro. In SVG, we find Shrewsbury, Queensbury, Queensberry and Edinboro. Although these places might be considered strategic locations overlooking the waters of SVG – for instance Fort Charlotte is overlooking Edinboro, and Queensberry Point is on the southernmost tip of Union Island – there have never been forts per se at these locations.

In the United Kingdom and Ireland, one of the most productive place naming suffixes is -shire, which denotes a district or county in the “Old English” of the Middle Ages. Typically, then, places named Berkshire Hill and Dorsetshire Hill would suggest that Berk and Dorset are towns in their respective counties, much like Gloucestershire and Yorkshire in England are the counties where the towns Gloucester and York can be found. Such is not the case in SVG. Needless to say, St Vincent, itself a name imposed by the colonial administrators to replace the indigenous name Iouloumain or Yurumein, was subject to the vagaries of the colonial gentry.

Moreover, the case of Dorsetshire Hill is an interesting example of how pronunciations and spellings can transform names over time. My guess is that a lot of Vincentians grew up saying “Dorstruh” Hill. In the UK context, Gloucester and Worcester sound somewhat like “Glostuh” and “Worstuh” to the Vincentian ear. It may well be that the “Dorstruh” pronunciation was not a local invention but rather that it was imported. With time, as the word became more often written, we resorted to spelling pronunciation. Today, the standard Vincentian pronunciation “Dorsetshuh” is commonplace.

Stubbs, St. Vincent. Stubbs was named after Mr Stubbs, a landowner in the area. (photo credit Robertson Henry)

In other cases, place names reflect personal names, be they landowners, governors or civil and military administrators whose legacies in the nation are esteemed to be worthy of commemoration. Thomas Fitzhugh was awarded land around the Richmond Vale area. Today, Fitzhughs can still be found on the map. George Henry Sharpe owned the Redemption estate. Redemption Sharpes is known to all and sundry in SVG. Edward Flemming Akers owned substantial land in the area still known as Akers. And we can relate Stubbs, Choppins, Frenches, Lowmans and Montrose to properties owned in those areas by Mr Stubbs, Thomas Choppin who owned property in Harmony Hall, Charles James French, George Lowman and council member, Andrew Rose. In her 1831 transcription of Ashton Warner’s Narrative, Susanne Strickland recorded that Ashton Warner was a slave on the Cane Grove estate owned by Mr Ottley. Ottley Hall is indeed in the vicinity of Cane Grove. Landowners from France also left their mark. We owe Questelles to Jean-Baptiste Questel, probably an absentee slave owner who had settled in St Bart.

Questelles, St. Vincent. Questelles was named after Jean-Baptiste Questel, probably an absentee slave owner who had settled in St Bart. (photo credit Robertson Henry)

With respect to personal names being used to designate places, there was a tendency to add the letter ‘s’ like in Choppins, Redemption Sharpes and Lowmans, or sometimes ‘es’ as in the case of Frenches. These letters indicate that the personal names were followed by the possessive marker (apostrophe ’s in writing). By the 18th century, it was commonplace to mark possession this way in writing. In a sense, this would mean that if we were dealing with writing, these would be rendered Choppin’s land, Sharpe’s estate or Lowman’s property but in spoken language the possessive apostrophe cannot show up. With time, the apostrophe mark fell out of use in written language leaving us with the bare ‘s’ or ‘es’.

Young Island, St Vincent. Young Island was once owned by William Young. (photo credit Robertson Henry)

However, adding the possessive marker to the personal names was not systematic because Samuel Greatheed left us simply Greathead, the La Croix family left us La Croix and the Ottley family left us Ottley Hall. It is obvious that locals hesitated about whether to express the possessive form or not. Do we continue to say Young’s Island, or should we simply refer to the island once owned by William Young as Young Island? The official SVG map has opted for Young Island.

Bridge across Ashton Lagoon in Union Island. The suffix ‘ton’ in Ashton meant “estate” or “farm” in Old English. (photo credit Bria King)

In place names like Clifton and Ashton the recurring suffix -ton meant “estate” or “farm” in Old English. These two toponyms may have been merely examples of transplanted place names. It is worth noting that, in earlier writings, St Vincent’s capital is recorded as Kingston. This is found throughout Valentin Morris’ “Narrative” in the 1770s, whereas we find Kingstown in Charles Shephard’s 1831 “Historical Account”. In place names like Cheltenham and Chatham Bay in Mustique and Union, the suffix -ham would typically mean “village” or “estate” in the UK context. These two place names can still be found in Gloucestershire and Kent. Your guess is as good as mine as to why these names held in Mustique and Union Island.

Equally noteworthy is the fact that “St Vincent” is not uniformly spelt throughout. We often find the spelling variant St. Vincent’s which has both the possessive apostrophe ’s and a period after the abbreviation of Saint. In fact, Standard British English would require us to eliminate the period based on the premise that a dot should follow an abbreviation whose final letter does not constitute the last letter of the full word. So, whereas Prof. requires a period, St does not require one if it is the short for Saint, nor does Mr if it means Mister.

Coulls Hill, St Vincent. Coulls Hill is a place name that came about from a mixture of personal names with a natural physical feature. (photo credit Robertson Henry)

Some place names came about from a mixture of personal names with a natural physical feature. This may have been the reason why Coulls Hill, Mount Wynne, Mount Rose, Mount Bentinck and Sharpesdale were so named. Thomas Coull owned land around Westwood. Robert Wynne and Andrew Rose were planters in the respective areas.

New Montrose, Kingstown, St Vincent. Montrose is an example of a place name that is a mixture of a personal name (Andrew Rose) and a natural physical feature (Mount) (photo credit Eldonte Samuel)

William Bentinck was the Governor who took St Vincent into the 19th century. Dale means “valley” and I suspect that Sharpe could refer to either of the Sharpe families on St Vincent. Besides George Henry Sharpe previously mentioned, Granville Sharp (note the spelling variant), who served on the Emancipation committee with Wilberforce in 1787, was also an influential figure internationally and worthy of commemoration.

Features are also reflected in place names like Falls of Baleine. In French, “baleine” means “whale”. Maybe to the name giver, the waterfall conjured up the image of a whale. Trinity Falls is a waterfall that cascades into a pool from three points, as the name suggests. Black Point and Mount Pleasant may have had features that stirred up related images to the name giver.

Port Elizabeth, Bequia. Port Elizabeth was named after the late Queen Elizabeth II. Bequia was given the name “Becouya”, meaning”Island of Clouds” by the indigenous people. (photo credit Clare Keizer)

Belvidere, from French, is literally a lookout point. Calder Ridge, Largo Heights, and Lower Bay are toponyms that speak for themselves. Port Elizabeth, Princess Margaret Beach (for royalty sake), Georgetown (in honour of King George) and Carenage – from a French word meaning “where ships are streamlined” – are also relatively transparent place names. Maybe less transparent are La Soufriere and Mustique. Although they are French-sounding, given their current spelling and pronunciation, they do not correspond to any standing French terms. Mustique reminds us of “moustique”, the French for “mosquito”, and Soufriere is an old French word derived from “soufre” meaning “sulphur”. In French, the word has fallen out of use, but it can be used to refer to sulphur mines particularly thanks to the fact that several volcanoes in the region carry the name.

Cane Garden, St. Vincent. Cane Garden was formerly a sugar cane plantation. (photo credit Clare Keizer)

Some place names, albeit descriptive, do not seem to say anything about the physical characteristics of the place. We may be lucky to still find a quarry at Quarry, some bamboo plants in Bamboo Range and Palm trees on Palm Island but the times when we could find sugar cane plantations in Cane Garden and Cane Grove are well behind us.

Glebe Hill, Barrouallie. A glebe is a piece of cultivable land, on which crops were produced for the Anglican priests or to bring in profits for the church.(photo credit Jada Chambers)

In other cases, the origin of the name might remain obscure to locals. The younger members of the Vincentian population may not readily make the link between Glebe Land and its original meaning. In fact, a glebe is a piece of cultivable land, on which crops were produced for the Anglican priests or to bring in profits for the church. Coxheath is a tricky place name. Was it transplanted directly from England or did it refer to uncultivated land belonging to either of the Cox family members on St Vincent? In Old English, “heath” denoted uncultivated land. The place name Coxheath is not unique to SVG since it can be found in Kent and in Nova Scotia.

Cumberland Bay. Cumberland is an example of a name that was transplanted to St Vincent. (photo credit Clare Keizer)

History and identity are strongly influenced by collective and individual attitudes to naming, as evidenced by many place names given by the settlers without any proven connection to the newly acquired territory: Brighton , Prospect, Cumberland, Richmond, Dumbarton and Glebe Land were boldly transplanted to SVG as well as to other colonies in the region and in the wider geographic sphere. For instance, Glebe Land can be found in Barbados and in Australia in addition to parts of the UK. The traveller to Canada, Australia and the USA is sure to find a place named Brighton. There is also a place named Dumbarton in Scotland.

Byera, St Vincent. Byera is an example of an indigenous name (formerly Bayira) which means “in opposition to” in the language of the Caribs. (photo credit Robertson Henry)

The British were not alone in copying onto the unknown territory place names which reminded them of their native land based on real or legendary similarities. The French also chose to name places according to the services they procured them. For instance, Petit Bordel needs no comment if not a glaring effort to rid the community and its people of the stigma the name has brought to generations of residents. The indigenous population also participated in the naming process and these place names reflect both their linguistic heritage and their functional approach to place naming. One such example is Bayira (spelt Byera today) which means “in opposition to” in the language of the Caribs. On the Treaty map of 1773, Bayira is where the English drew the territorial boundary that the Caribs where forbidden to go beyond.

Barrouallie, St Vincent. Barrouallie is another example of an indigenous place name. It was formerly spelt ‘Barouli’ (photo credit Jada Chambers)

In a short note published in 1956, Douglas Taylor put forward several examples of indigenous place names on St Vincent. Many of them have fallen out of use and have been replaced by English-sounding ones. Some of these names can be found in Nathaniel Uring’s writings, Valentine Morris’ “Narrative” and Charles Shephard’s Historical account but often with varying spellings. In these documents, Owia is written as Oya, Bequia as Beakway, Barrouallie as Barouli and Barrowli, Biabou as Bayabou and Rabacca as Rabaca.

Biabou, St Vincent. Biabou is an example of an indigenous place name. It was formerly spelt Bayabou. (photo credit Robertson Henry)

Layou is another indigenous place name that also exists in Dominica where the Kalinago also made their home. Douglas Taylor, an authority on Island Carib (Kalinago) language states in a piece published in 1956 that it is ‘Indian’ but he did not attempt to give a specific etymology or meaning. In Dominica, there is also a river called Layou River. We can only assume a Kalinago origin for SVG Layou as well. The British tried replacing Layou with Ruthland Bay but the indigenous name stood its ground.

There is also a startling amount of instability hampering the retention of these names since competing or alternative names are often offered. So, Fort Sackville is an alternative name for Owia; Fort Guilford could replace Rabacca, Fort Hilsborough is in competion with Colonarie, Princes Town or Queen’s Bay appeared alongside Barrouallie, and Fort Dalrymple is used in place of Bayabou. In the 1823 map I referred to earlier on, Suffolk Bay had replaced Troumaca Bay. This example shows that indigenous names sometimes won over European place names, but this is quite rare. Cubiamairou lost to Stubbs, Kingstown got the edge over Washigunny or Ouashegunny and Saint Vincent is symbolically called Iouloumain or Yurumein only by a few people today. And despite the fact that some indigenous names endure, as do Canouan, Wallibou and Battowia, they represent a highly reduced number of occurrences compared to olden days. As such, place names in SVG do not reflect the melting pot that could otherwise be used to qualify its social landscape and its people.

Manning Village, St Vincent. This village was named in honour of former Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago Patrick Manning. (photo credit Robertson Henry)

There is a glaring need for study of place names in the Caribbean in general and in SVG in particular. Although there may be naming processes that are common to the region, in each nation there are distinct social and political factors which might take place-naming into directions not yet charted. Another contributing factor has to do with subtle changes in spelling or, more impactfully, with informal or individual naming practices which catch on in the public sphere and possibly with local authorities.

A good example of this is how Manning Village found its way into our registers. The 3rd July 2016 edition of the Trinidad and Tobago Guardian relates that the villagers themselves sought to commemorate the deceased T&T Prime Minister, Patrick Manning, for his government’s generous grant aimed at acquiring new lands around Byera to relocate them in the wake of the damage caused to their homes by Hurricane Ivan in 2004. Are we up to incorporating place names like Baghdad, Hollywood and Bombom into our maps anytime soon? Such informal names tell us a lot about the present state of social affairs in our nation and are likely to be passed on to succeeding generations.

Irrespective of the extent to which we feel the nation’s history is represented through place names, we have inherited a past that has built part of our nation’s identity and, by extension, part of our identity as nationals. What’s in a name? Each of us would need to determine, individually, how much of that identity we are willing to embrace. Place names are locators of memory. They offer individuals, individually or collectively links to their past, allow grounding and ensure continuity with our history.

[[UPDATED on Thursday, January 5, 2023 at 8:36 am AST to include the origin of the Layou place name.]]

Before being appointed Associate Professor of French Linguistics and Didactics at the Université de Picardie Jules Verne (France) and part-time Lecturer at the Universität Bielefeld (Germany), Paula Prescod taught English and French to speakers of other languages in SVG and in France. She holds a Ph.D. in Linguistics from the Université Paris III, Sorbonne-Nouvelle. Her research and publications focus on linguistics, didactics, language use and the Caribs of SVG from a socio-historical perspective.